Martin (1992: 40):

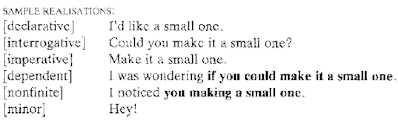

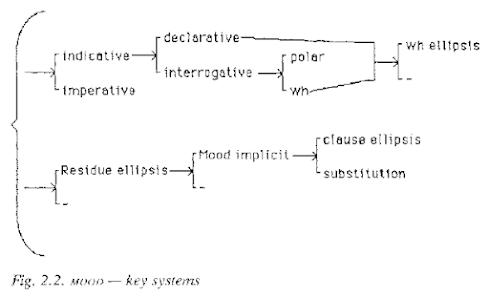

The question of how many layers of meaning to recognise raises the problem of units: just what unit is it to which speech function is being assigned? Is for example the response Yes, I would, thank-you, but make it a small one. one speech act or two (or more)? Given what has been stressed to this point about the grammar making available resources for structuring dialogue the most appropriate unit would appear to be a clause selecting independently for MOOD. This rules out the embedded and hypotactically dependent clauses illustrated below:

They loved the team that won. (defining relative)

They defeated whoever they met. (nominalised wh clause)

They watched Manly winning. (act)

It pleased them that Balmain lost. (fact)

They wondered if they'd win. (hypotactic projection)

They won, which surprised them. (hypotactic expansion)

But it does admit paratactically dependent clauses, which do select independently for MOOD. Note the variation in MOOD possible after but, showing that the but is introducing a new move:

Yes, I would, thank-you, but make it a small one.

Yes, I would, thank-you, but I'd like a small one.

Yes, I would, thank-you, but could you make it a small one?

Blogger Comments:

[1] As previously explained, Martin misunderstands all strata as "layers of meaning" (even phonology!), because he confuses strata (meaning-wording-sounding) with semogenesis ("all strata make meaning").

[2] This is a non-sequitur. The number of strata ("layers of meaning") has no bearing on "the problem of units", since the latter is only concerned with one stratum, irrespective of the number of strata.

[3] To be clear, Halliday (1985: 68) "assigns" speech function to the clause as interact or exchange.

[4] To be clear, this instance involves two major speech functions:

Yes, I would [statement]

but make it a small one [command]

[5] Although it is true that such clauses are presented as presumed rather than negotiable (Halliday & Matthiessen 2014: 172), embedded and dependent clauses can realise speech functions, and can "select independently" for MOOD. For example, in:

Did anyone see [[ if the policeman shot him ]]?

the ranking interrogative clause realises a question, whereas the rankshifted declarative clause realises a statement; and in:

Was anyone here || when the policeman shot him?

the dominant interrogative clause realises a question, whereas the dependent declarative clause realises a statement. Other combinations are, of course, possible, as demonstrated by the imperative clause realising a command and declarative clause realising a statement in:

Don't shoot every policemen just because one of them is a murderer.

Moreover, in an exchange, an interlocutor can respond to a dominant clause, dependent clause, or embedded clause:

Robin said that Lise saw Tom cheating at cards.

— He said no such thing! (reply to dominant clause)

— She couldn't have! (reply to dependent clause)

— But he wasn't! (reply to embedded 'act' clause)

.png)