Martin (1992: 45):

Significantly, attitude is not realised through the Mood function in English, unlike MODALISATION and MODULATION which can be expressed through modal verbs and adjuncts. For this reason ellipsis in English does not facilitate the negotiation of attitude — the attitude to be graded is commonly realised in the Residue itself.

It thus follows from the grammar that how a speaker feels is less commonly negotiated through pair parts in dialogue than is inclination, obligation, probability and usuality and that where it is negotiated, MODALISATION and MODULATION are typically being negotiated as well since the Mood element is normally present (cf. Yes he is rather above).

Blogger Comments:

[1] The argument here is:

Premiss: attitude is realised in the Residue not the Mood elementConclusion: ellipsis does not facilitate the negotiation of attitude

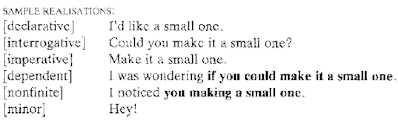

To be clear, this is a false conclusion invalidly argued from a false premiss. The premiss is false because attitude can be realised in the Mood element as well as the Residue, as demonstrated by:

The conclusion is false because ellipsis can "facilitate the negotiation of attitude", as demonstrated by exchanges like:

Is he scrupulously honest?— No,he isn't scrupulously honest.— Yes, he isscrupulously honest

[2] To be clear, this does not follow from the grammar, see [1] above. Moreover, it is bare assertion, unsupported by evidence from corpora.

[3] The argument here is:

Premiss: the Mood element is normally present.Conclusion: MODALISATION and MODULATION are typically being negotiated.